Incredible 1861 Letter by Private Albert F. Sharp, 2nd Connecticut Volunteers — First Battle of Bull Run — "We took several prisoners and killed a Colonel of a South Carolina Regiment"

Incredible 1861 Letter by Private Albert F. Sharp, 2nd Connecticut Volunteers — First Battle of Bull Run — "We took several prisoners and killed a Colonel of a South Carolina Regiment"

“As we—Col. Keyes' Brigade—were advancing by the right flank to sustain the first Conn. and fifth Mass. Reg., who were engaged with the enemy, we come upon several of the wounded of the rebel forces. One was a Georgian who was badly wounded in the forehead. A cold, clammy sweat covered his face. His lips were white and trembling. Death was in earnest for his victim and there was no hope. I bent weeping over the suffering man and begged for him a cup of water. This revived him a little, but yet unable to speak, he smiled gratitude and then he died.”

Item No. 3447639

In this richly detailed battle letter written by a member of the 90-day 2nd Connecticut Volunteers, Private Albert F. Sharp recounts his experience during the Union disaster at the First Battle of Bull Run.

The letter was written on July 31, several days after the July 21 battle. In the letter's opening lines, Sharp expresses the physical and emotional exhaustion he feels. "A march of sixty miles in a few hours," he writes, "little food, little water, long continued and exhausting labor of the battlefield, innumerable provisions, and days of weary watching under arms has proved too much for me. I seek rest but find none." He continues:

I have not yet been able to disconnect my mind with the scenes of the 21st inst. So appalling were many of the sights which met my gaze. Whichever way I turned my eye on this memorable sabbath, my heart sickened, and the impression received lingers with me in all the freshness of the hour which gave them birth.

He then recounts how his regiment, as part of the brigade commanded by Colonel Erasmus D. Keyes, maneuvered into position for an attack on the Confederate positions on Henry Hill:

As we—Col. Keyes' Brigade—were advancing by the right flank to sustain the first Conn. and fifth Mass. Reg., who were engaged with the enemy, we come upon several of the wounded of the rebel forces. One was a Georgian who was badly wounded in the forehead. A cold, clammy sweat covered his face. His lips were white and trembling. Death was in earnest for his victim and there was no hope. I bent weeping over the suffering man and begged for him a cup of water. This revived him a little, but yet unable to speak, he smiled gratitude and then he died.

Sharp then describes the attack that followed, during which the death of a "Col. of a South Carolina Reg'mt" particularly affected him:

We soon changed our position from that we had first taken, and marched by the left flank. The original object of this was to charge on one of the largest and most important of the rebels’ sand batteries. Subsequently, Gen. Tyler discovered that this could not be done except at a great sacrifice of men on our side, consequently abandoned his purpose, and continued to march us at the first to reconnoiter the enemy' s position. During this march we took several prisoners and killed a Col. of a South Carolina Reg’mt. This was an awful event. God forbid that I shall ever witness it repeated. After this we were for an hour exposed to an awful cannonading. It is a miracle that any of us escaped death.

The rebels facing the Connecticut men belonged the Hampton Legion of South Carolina, whose Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Johnson was struck in the head while encouraging his troops. Some sources suggest Johnson was hit by a musket ball, while others indicate it was a cannonball. Sharp's reaction to the event suggests that perhaps it was the latter.

The attack failed to dislodge the rebels from their positions. When other federal assaults on Henry Hill failed later that afternoon, the rebels counterattacked, sending panic through the federal ranks. It turned into a rout. Sharp next describes scenes of pandemonium during the retreat:

About five o’clock P.M. order come to retreat, which we did from the field in order, our ranks being confused only when the N.Y. troops broke through our line. Having reached our hospital half a mile from the battlefield, many of my fellow soldiers were crying in agony, some with their faces downwards to the earth, others reeling in for support across the fence, and others crawling on their hands and knees for some place of safety from the rebel cavalry.

In the retreat, many of our wounded troops mingled with the throng. I saw on horseback one man with a broken leg, another with his arm pierced with a musket ball. Far to the rear and on foot come others more or less afflicted. Among the number was a young man streaming with blood. When we arrived at Germantown, a good union woman comforted the man as much as possible, then bade him God speed, and with weeping which amounted almost to wailing, urged the troops to stand by the old flag.

At the conclusion of his letter, Sharp sums up his feeling about the actions of the rebels and predicts that "God will not always suffer this to be so." He writes:

The southerners behaved more like barbarians than civilized men. Beside burning our hospital and bayoneting our wounded on the field, they took nearly all our sergeants prisoner, thereby depriving our suffering troops of the little means of relief they had at hand. God will not always suffer this to be so. He will avenge His own elect, and that right early. My confidence is strong in the final triumph of our arm and suppression of the ungodly rebellion.

Sharp signs as "Alie." We can identify him as the letter’s author because of another Sharp letter preserved in the Library of Congress.

Sharp would muster out with the 2nd Connecticut at the conclusion of his enlistment in early August, but in September would enlist for three years in the 10th Connecticut. He would serve with the 10th until August 1864, when he would receive a mortal wound at the Battle of Deep Bottom that he would succumb to four days later, on August 18, 1864.

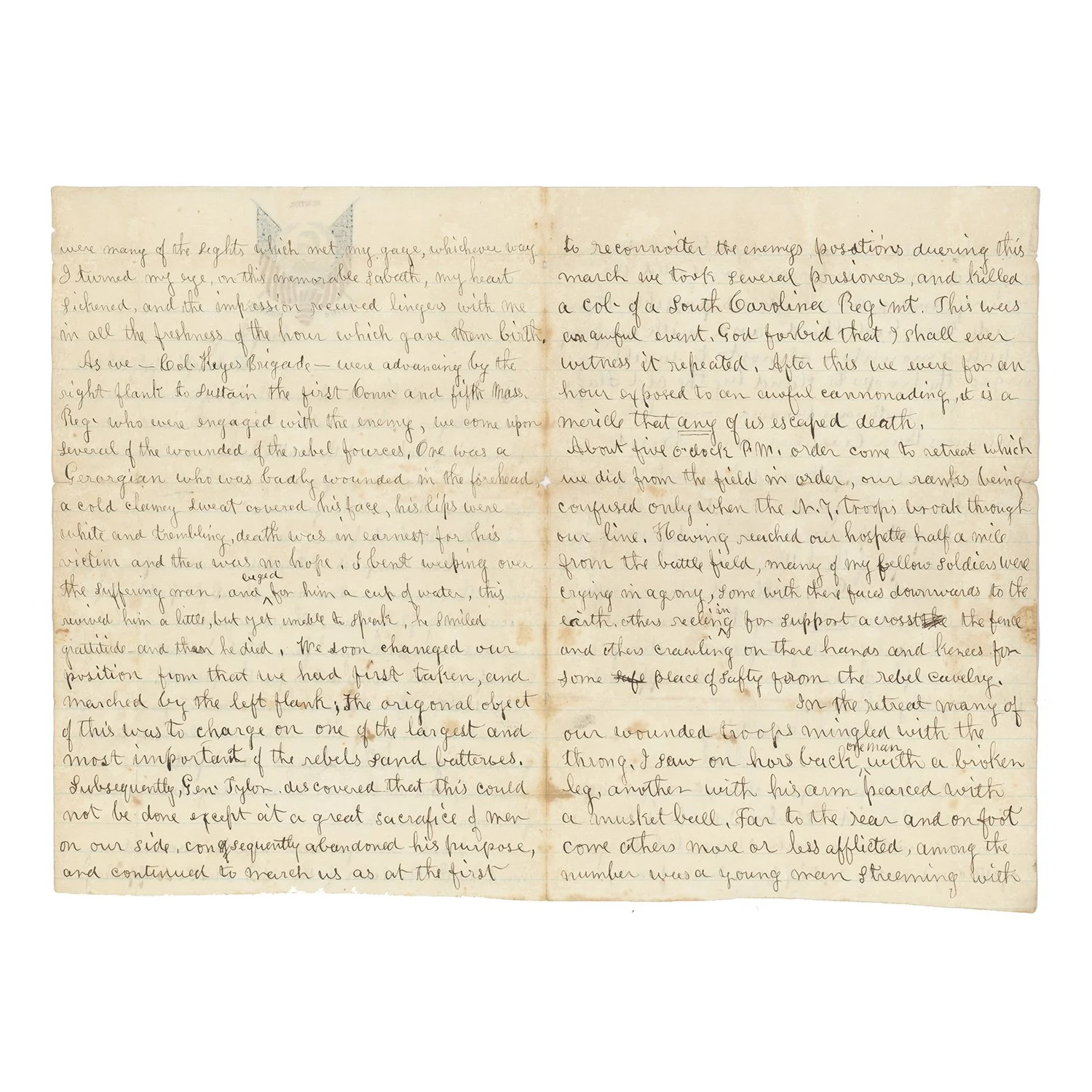

The letter was written on four pages of a bifolium letter sheet measuring about 5 5/8” x 8 1/24”, which bears a rare patriotic decoration of Major Robert Anderson of Fort Sumter fame. Light foxing and toning. Creased at the original folds. The full transcript appears below:

Camp Keyes

Washington July 31st 1861

Dear ones at Home:

A march of sixty miles in a few hours, little food, little water, long continued and exhausting labor of the battlefield, innumerable provisions, and days of weary watching under arms has proved too much for me. I seek rest but find none.

Our camp is situated in an open field where there is not a tree nor a shrub to protect us from a scorching July sun. The consequence is I am becoming more and more sickly. I fear that I shall be obliged to suspend all camp duties for the present.

No doubt a few days at home would greatly relieve me, and a change of diet restore me soon to my former vigor. These changes I anticipate with much pleasure, and all the more so as the day draws near for our return home.

I have not yet been able to disconnect my mind with the scenes of the 21st inst. So appalling were many of the sights which met my gaze. Whichever way I turned my eye on this memorable sabbath, my heart sickened, and the impression received lingers with me in all the freshness of the hour which gave them birth.

As we—Col. Keyes' Brigade—were advancing by the right flank to sustain the first Conn. and fifth Mass. Reg., who were engaged with the enemy, we come upon several of the wounded of the rebel forces. One was a Georgian who was badly wounded in the forehead. A cold, clammy sweat covered his face. His lips were white and trembling. Death was in earnest for his victim and there was no hope. I bent weeping over the suffering man and begged for him a cup of water. This revived him a little, but yet unable to speak, he smiled gratitude and then he died.

We soon changed our position from that we had first taken, and marched by the left flank. The original object of this was to charge on one of the largest and most important of the rebels’ sand batteries. Subsequently, Gen. Tyler discovered that this could not be done except at a great sacrifice of men on our side, consequently abandoned his purpose, and continued to march us at the first to reconnoiter the enemy's position. During this march we took several prisoners and killed a Col. of a South Carolina Reg’mt. This was an awful event. God forbid that I shall ever witness it repeated. After this we were for an hour exposed to an awful cannonading. It is a miracle that any of us escaped death.

About five o’clock P.M. order come to retreat, which we did from the field in order, our ranks being confused only when the N.Y. troops broke through our line. Having reached our hospital half a mile from the battlefield, many of my fellow soldiers were crying in agony, some with their faces downwards to the earth, others reeling in for support across the fence, and others crawling on their hands and knees for some place of safety from the rebel cavalry.

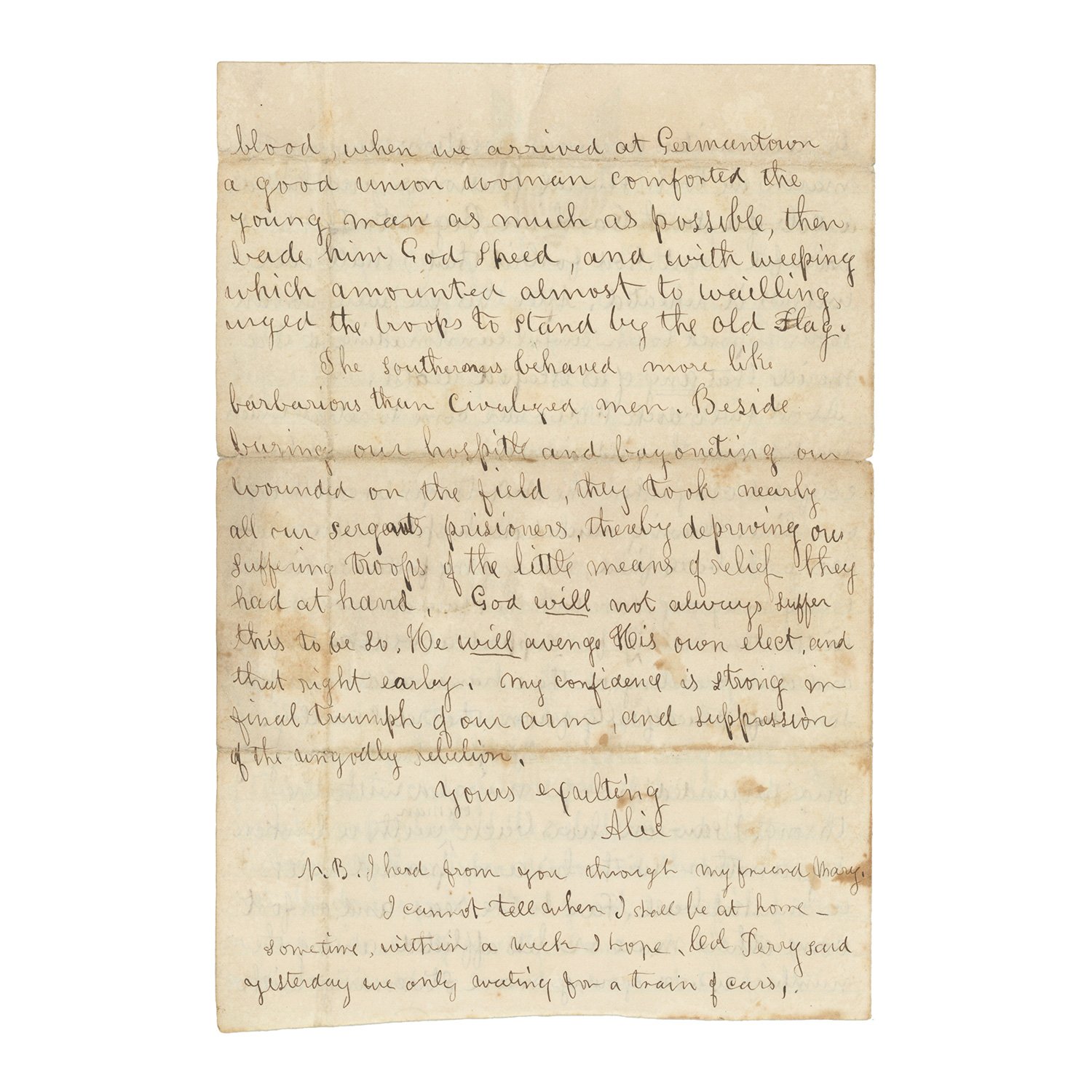

In the retreat, many of our wounded troops mingled with the throng. I saw on horseback one man with a broken leg, another with his arm pierced with a musket ball. Far to the rear and on foot come others more or less afflicted. Among the number was a young man streaming with blood. When we arrived at Germantown, a good union woman comforted the man as much as possible, then bade him God speed, and with weeping which amounted almost to wailing, urged the troops to stand by the old flag.

The southerners behaved more like barbarians than civilized men. Beside burning our hospital and bayoneting our wounded on the field, they took nearly all our sergeants prisoner, thereby depriving our suffering troops of the little means of relief they had at hand. God will not always suffer this to be so. He will avenge His own elect, and that right early. My confidence is strong in the final triumph of our arm and suppression of the ungodly rebellion.

Yours exalting

Alie

N.B. I heard from you through my friend Mary. I cannot tell when I shall be at home. Some time within a week, I hope. Col. Terry said yesterday we only waiting for a train of cars.