Signed CDV of Lieutenant Edward Stanley Abbot, 17th US Infantry — Mortally Wounded Near Little Round Top at Battle of Gettysburg

Signed CDV of Lieutenant Edward Stanley Abbot, 17th US Infantry — Mortally Wounded Near Little Round Top at Battle of Gettysburg

Item No. 3047132

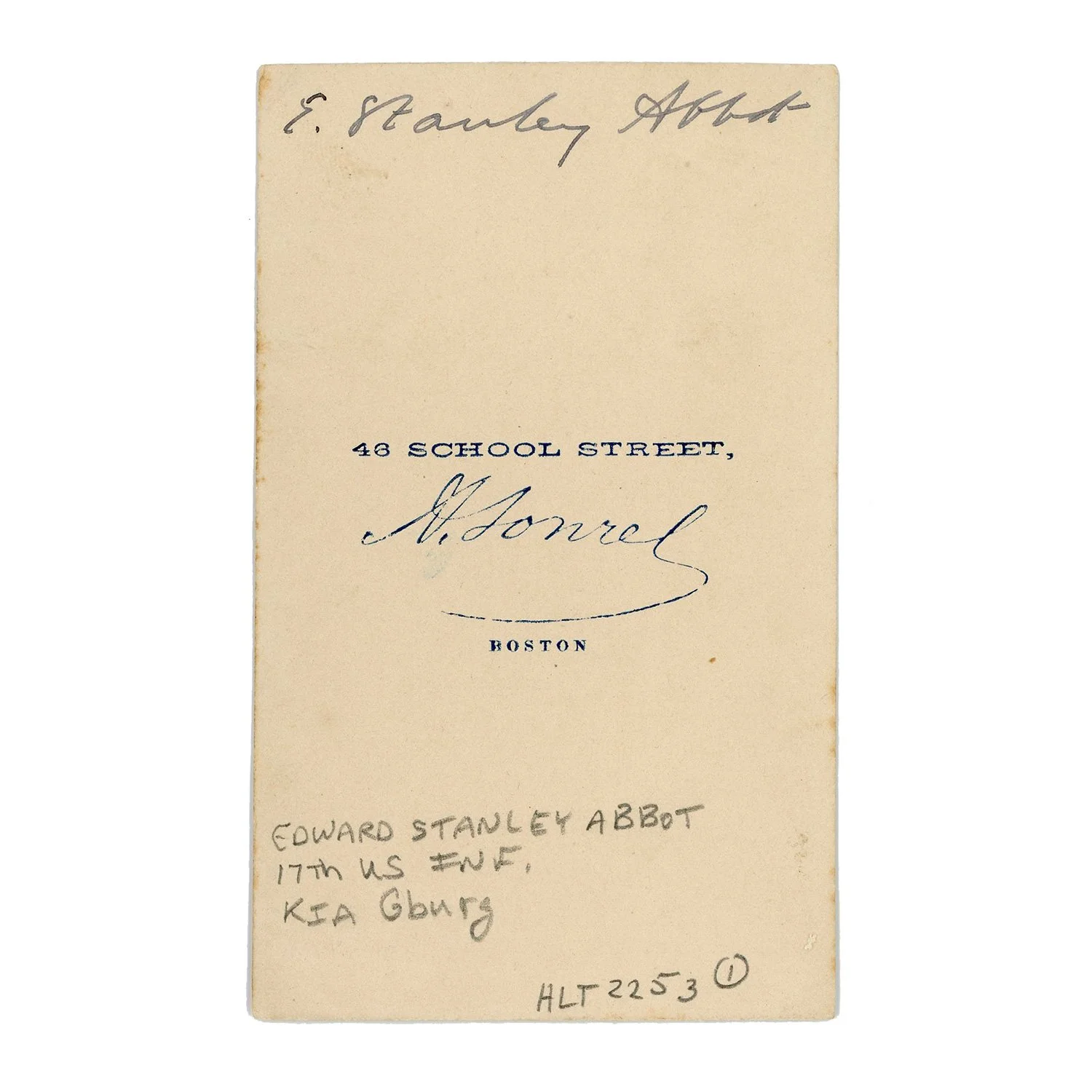

The young officer featured in this bust-view CDV image is First Lieutenant Edward Stanley Abbot of the 17th US Infantry, who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg, July 2, 1863. He died of his wounds in a Fifth Corps hospital six days later on July 8. On the reverse of the carte is Abbot’s ink signature over the imprint of Boston photographer A. Sonrel. A modern pencil inscription appears under the imprint. Measures about 2 1/2” x 4”.

The following biography appears in Harvard Memorial Biographies, Vol. II, edited by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and published in 1867 by Sever and Francis, Cambridge. It also appears on Abbot’s Find-a-Grave page. It was written by Abbot’s brother, Edwin Hale Abbot.

1864. EDWARD STANLEY ABBOT. Second Lieutenant 17th United States Infantry, November 10, 1862; First Lieutenant, April 27, 1863; died July 8, 1863, of wounds received at Gettysburg, Pa., July 2.

EDWARD STANLEY ABBOT was born at Boston, October 22, 1841, and was the son of Joseph Hale and Fanny Ellingwood (Larcom) Abbot. He was fitted for college partly at the Boston Latin School, the private Latin School of E. S. Dixwell, Esq., and Phillips Exeter Academy, and partly by an older brother. He entered Harvard College in July, 1860, after passing an excellent examination. In September, 1861, he was absent from College a short time on account of his health, and soon after his recovery began to devote his whole time to military study, with the design of becoming an officer in the Regular service. He closed his connections with the College in March, 1862, and went to the Military School at Norwich, Vermont, where he stayed about four months. On July 1, 1862, he enlisted at Fort Preble, Portland, in the Seventeenth Infantry, United States Army, having previously declined to accept a commission in the Volunteer service, because he chose to take what he deemed the shortest road to a commission in the Regular service. The absence of his brother, now Brevet Major-General Henry L. Abbot, then an engineer officer on General McClellan's staff in the Peninsula, had occasioned some delay in obtaining the commission he wished for. He therefore took this manly way to earn one for himself, under a promise from Lieutenant-Colonel J. Durrell Greene, of the Seventeenth Infantry, that, if he showed himself fit for a commission, he should be recommended to the War Department to receive one. "In four months and ten days I was enabled," he says in a note-book, "to regain the position of a gentleman, which I had voluntarily resigned; — a few days? an infinity of time!"

He once remarked to a friend, in reference to this period of his life, that he thought nothing but the music of the band and the magnificent ocean view down Portland Harbor had enabled him to endure it. On the 11th of November, 1862, he received the commission of Second Lieutenant, and, at his own request, was at once assigned to duty with a company of the battalion then in the field with the Army of the Potomac. Early in December, 1862, he left his home for the last time, taking on a party of recruits, about fifty in number. Though the only officer with the party, and himself so young, he carried the entire number through Boston, New York, and Washington without the loss of a single man. For this service, an unusual one, he received much commendation at the time from his superiors. He became First Lieutenant on April 27, 1863.

He never came home again; and indeed, during his whole military career, he was absent from duty only three days, which he spent in the defences of Washington on a visit to General Abbot, whom he had not seen for two years. He rejoined his company in the Chancellorsville campaign, having walked twenty miles in one night to overtake them before the battle, in which his regiment took gallant part, and lost one man in every ten. He shared in the terrible forced marches by which the army reached Gettysburg, — unsurpassed, if they have been equalled, during the whole war. His regiment reached the battle-ground on Thursday morning at dawn, and was stationed on Little Round Top, near the extreme left of our line.

The attack of the Rebels began about four in the afternoon. Early in the fight, while leading his men in a charge down a hill across a marsh and wall and up a little slope, Stanley was struck in the right breast by a minie-ball. The shoulder-strap on the light blouse he wore had worked forward, and the ball, just stripping off some of its gold-lace, passed through the right lung and lodged near the spine. He fell senseless to the ground, and for some hours was unconscious. He was at once borne to the rear, though not expected to survive long. He afterwards rallied, however, and lived until about noon of July the 8th, when he died in the field hospital of the Second Division of the Fifth Army Corps. His regiment lost fearfully in this battle, fourteen out of the nineteen officers who were there present being wounded.

The Class-Book, in a sketch intended, when it was written, for Stanley's classmates only, contains the following narrative of his last days.

"On Tuesday forenoon, 7th July, I was sitting in my office in Boston, when I received the following telegram from Baltimore, the last words I ever received from my brother: 'Wounded in the breast. Doctor says not mortal. I am at corps hospital, near Gettysburg. Expect to be in Baltimore in a few days. E. Stanley Abbot.' I started at once, by the next train, to take care of him; but, though using the utmost possible speed, I could not, so impeded was communication, reach Gettysburg until Friday, the 10th, two days after his death. A brother officer, who lay by his side until he died, told me that Stanley, when he first became conscious, sat up, and spoke in a full, natural tone. He lay in a hospital tent on some straw. The tent was pitched in a grove on a hill, around the foot of which a beautiful brook flowed. On Tuesday morning, when the surgeon, Dr. Billings, of the Regular service, came in, Stanley asked the Doctor to feel his pulse, and desired to know if he was feverish, since the pulsations were at one time strong and quick and then slow and feeble. Dr. Billings, a most excellent surgeon and a very prompt and straightforward man, felt of the pulse, and then, looking Stanley in the eye, slowly answered, 'No, Mr. Abbot, there is no fever there. You are bleeding internally. You never will see to-morrow's sunset.' Captain Walcott, the officer at his side, who related these circumstances to me, says that he then looked at Stanley, to see the effect of these words. But Stanley was entirely calm. Presently he said, with a smile,'That is rather hard, isn't it? but it's all right; and I thought as much ever since I was hit.' Dr. Billings asked him if he had any messages to leave for his friends. Stanley said he would tell Walcott everything; saying, too, that I should come on there, and that everything was to be given to me. Dr. Billings then left him.

"As Stanley lay without speaking, Captain Walcott, who is a deeply religious man, spoke to him, and inquired if Stanley had any messages to leave with him. Stanley replied, 'No.' Walcott continued, 'Have you a father and mother living?' ' Yes.' 'Are they church-going people?' 'Yes.' 'Then,' said Walcott,' if your mother knew how you are, she would wish you to pray.' Stanley turned his face toward his comrade, very quietly, and then answered slowly, 'That point was settled with me long ago.' He did not talk much, but lay quite still. The officers who were there told me they never saw anyone more quiet and free from agitation. His right arm was disabled, so that he probably could not write. He was among comparative strangers, and no word so transmitted would have been much for him to say or for us to receive. He knew it was too late to say he loved us, if we did not know that before. He rightly chose rather to trust to our understanding how he felt, without attempting to put his feelings into words, than to lay his heart bare before those who knew him so little, and whose own troubles were enough for them to endure. And so life slowly passed away. He lived long enough to understand that he died in victory, and that his blood was not lost. He spoke pleasantly to those about him, and to the last took a kindly interest in their welfare. On Wednesday morning, about eleven o'clock, when he was very near his end, and probably had lost distinct knowledge where he was, some of the other wounded officers were speaking of being carried to Baltimore by private conveyance, and, when Walcott proposed that they should all do so, Stanley spoke up clearly, and said, — they were his last words, — 'Walcott, I'll go with you.' Soon after he died without a struggle, and his warfare was over.

"The condition of things at Gettysburg after the battle beggars description. One fact alone is enough to indicate it. For five days after my arrival, I could not obtain, in any way, a coffin in which to bring his body home. At last I succeeded, by a happy chance; and hiring two men, a horse and a wagon, I started about two o'clock for the camp hospital. It was situated about five miles from the town, off the Baltimore pike, on the cross-road, at the white church. It was a dull, rainy, very warm afternoon, and on every side was the mark of dreadful devastation. Surgeon Billings, who was in charge of the field hospital, a mere collection of huts, sent a soldier to guide me to my brother's grave. It was on a hillside, just on the outskirts of the grove in which the camp was pitched. The brook rolled round its foot in the little valley, while in the distance was Round Top, and the swelling landscape peculiar to that portion of Pennsylvania, — a family of hills, stretching far and near, with groves dotting their sides and summits. Here was the spot which, ten days before a lonely farm, was now populous with the dead.

"My brother's grave was marked carefully with a wooden headboard, made from a box cover, and bearing his name, rank, and day of death. It was so suitable a place for a soldier to sleep, that I was reluctant to remove the body for any purpose. But the spot was part of a private farm; and as removal must come, I thought it best to take the body home, and lay it with the dust of his kindred. When my companions had scraped the little and light earth away, there he was wrapped in his gray blanket, in so natural a posture, as I had seen him lie a hundred times in sleep, that it seemed as if he must awake at a word.

"Two soldiers of the Eleventh Infantry, the companion regiment of the Seventeenth, had followed me to the spot, — one a boy hardly as old as Stanley, the other a man of forty. As the body was lifted from the grave, this boy of his own accord sprang forward, and gently taking the head, assisted in laying the body on the ground without disturbing it, a thing not pleasant to do, for the earth had received and held it for a week. I told them to uncover the face. They did so, and I recognized the features, though there was nothing pleasant in the sight. I then bade them replace the folds of the gray blanket, his most appropriate shroud, and lay the body in the coffin. They did so ; but again the boy stepped forward, and of his own motion carefully adjusted the folds as they were before. When we turned to go, I spoke to the boy and his companion. They said they knew Stanley, and knowing I had come for his body, they had left the camp to help me, because they had liked Stanley. 'Yes,' added the boy, 'he was a strict officer, but the men all liked him. He was always kind to them. That was his funeral sermon. And, by a pleasant coincidence, as one of the men remarked to me on our way back, the sun shone out during the ten minutes we were at the grave, the only time it had appeared for forty-eight hours.

“His body now rests in the family burial-place in the churchyard at Beverly,—a pleasant place among the trees on a sloping hill, where one can see the sea in the distance, and at times hear the waves upon the beach,—a spot he had often admired in former times, and such as he would himself have chosen. It was a lovely summer afternoon at sunset when his friends gathered at the grave to leave the body in its last resting-place. The sky was full of sunshine and white fleecy clouds. The earth was green after a storm, and the distant sea blue as the heavens above; and it was impossible to resist the cheerful consolation which even Nature seemed to give. Rev. James Reed, my old school fellow and college chum, who had known Stanley from the day he was a little child, spoke the last words at his grave; and so the short story of his life was ended.

"I have designedly dwelt upon the pleasant things which then and now threw around the death of my brother an atmosphere almost of happiness, and certainly of peace. He had lived faithful, and he died in his duty. He is safe forever. He never will be less good, less true-hearted, less loving than we knew him; and life is well over when it is a good life well ended."

I will now say something of the last three years of his life, and quote a little from notes found among his papers and from letters. His cherished plan from boyhood up was to become an author. I now have many manuscripts of his, — stories, plays, songs, and the like, — and it may be that among them there is something worth preservation. For this purpose he went to College, carefully guarding from almost every one his secret. This was his ulterior design in entering the Regular Army. In February, 1862, he writes: —

"After the war ends, supposing I survive it, I should be stationed in some fort, probably, which would give me ample time to prosecute my plans in writing. I should have a settled support outside of literature (an inestimable blessing to a litterateur), and should be admirably placed to get a good knowledge of character and affairs, so necessary to a writer in these days. My objects remain the same, and I shall always pursue them while I live; but the means of obtaining those objects I wish to seek in a different way from the one I had marked out for myself. / must be a man, and fight this war through. That is the immediate duly; but that accomplished, — as a few years at furthest must see it accomplished, — and I can honorably take up once more the plans I have temporarily abandoned. It will be too late to return to college; and the army is the only place for me. When I shall have saved enough to support me, then I will resign, and give my whole time to my beloved plans, which in the mean time I shall not have been compelled wholly to neglect. May I have such a fate before me, if I live! Such a one as Winthrop, if, more happy, I should die!" In December, he writes again: —

"I certainly believe that I have a talent for writing. I actually think that, if I live to be thirty-five, I shall have written the greatest and noblest novel that ever was written. And yet I submit that it is an open question as yet whether I am an ass or not. If I write the book, I simply appreciated myself. If I fail to do so, why, I will be content with a pair of long ears instead of a laurel crown.

I think that is fair, so I won't begin to call myself names yet.

I have satisfied my personal ambition completely. I am a gentleman in station, with a sufficient income to keep the wolf from the door. That is all I wanted for myself. I don't care for rank or money, or anything of the sort. I will be a good officer, and as long as this war continues I will use every power God has given me to make God's cause triumphant; but still all this is the preface to my real work, — is simply putting coal into the engine. If I am really going to do a great work in the world; if, in fine, I am to be a worker in God's vineyard, I must do my work by writing. I know this, am sure of it. If I live and don't accomplish it, I shall have buried my talent."

And once more he writes: —

"Alas! what a contemptible thing is enthusiasm to one who does not sympathize in its object! I hope my enthusiasm is wiser and more manly; but, then one can have more impartial judges than one's self. O for a measure to measure things by! What would I not give to know whether I am an ass or a genius, a coward or a hero, a scoundrel or a saint! Ah, Mynheer, the Country Parson, would smile at that last sentence. I seem to hear from his half-sneering, half-pitying lips, 'My dear fellow, please steer between Scylla and Charybdis.' A fig for such philosophy! It is a priceless happiness to aim at the highest mark, and never dream of missing it. To be sure, if we fail, like the archers that strove for the hand of the Fairy Princess, death is the penalty. Well, who would not run the risk of hell for a simple chance of heaven? Every one but a craven. Down with mediocrity and its laudators. It is better to live a day than to vegetate a century. Enthusiasm, ambition, conflict, and victory,—these make life. All the rest are but the wearisome ceremonies of the soul's funeral."

These words I quote from his private papers, seen by no eye but his own while he lived. They are enthusiastic, for they are written by one quite young. They were visions in the air, for the wisdom of Divine Providence had allotted to him that which he speaks of as "the greater happiness." I have copied these words because they show what was the secret of his life, and because his ambition was a generous and noble one, of which no one need be ashamed. He practically trained himself for an author's work, as is shown by a little incident of which he told me in almost the last conversation we ever had. While he was in the Freshman year, a former friend had fallen into temptation, and embezzled fifty dollars from his employer. In despair, he told Stanley. Stanley at once, without saying anything of his design, wrote some stories, sold them, got the fifty dollars, and gave them to the boy. He mentioned this casually to me as a piece of Quixotry, which had caused some neglect in his college duties, for which I had blamed him at the time. What his future would have been, we may not say. I speak of these things to show what were his day-dreams, before his short and active life of manly duty ended.

At Cambridge he was of a reserved disposition, and lived much alone. He was poor, and was dependent upon aid which he trusted to repay in the future. Such a position often engenders some bitterness even in a true spirit of independence. He would not accept aid, except on the condition of being allowed to repay it afterwards. Still, being unable to do all which he liked to do, he chose rather to withdraw from companionship than to enter it on any terms which he thought would not suit this spirit. And if in his desire to stand alone there was something of the unripeness of youth, time would have mellowed the fruit.

He was thoroughly alive to the elements of romance in a soldier's life, as appears in the two following passages from his private notes: —

"On Christmas night (1862) I crept into my bed, and floated off into the fairy-land of dreams and fancies, until sleep threw its spell over me, as is my boyish and absurd wont. But suddenly my waking dreams seemed almost to haunt my slumbers. The softest music sounded through the stillness of midnight; and it was long before I could persuade myself that the strains were real, and not imaginings. The band of the Second Infantry was playing Christmas anthems in the midst of the sleeping army. The dreamy music, soft and low as a mother's prayer, floated over the camp, and stole like a benediction into the half-unconscious ears of the rude soldiery around. First it was a dead march; then a beautiful variation on 'Gentle Annie,' and last, 'Do they miss me at home?' The effect was unequalled by anything I ever heard, except that wonderful death chant which breaks in upon and hushes the mad drinkers of the poisoned wine in 'Lucrezia Borgia.' That is the beauty of a soldier's life. There are such touches of purest romance, occasionally breaking through the dull prose and bitter suffering. It is, after all, the only profession which rises above the commonplace. In it beauty and effect are studied and arrived at; and the most delicate refinement and heroism are necessary to the true soldier. It is that which is so charming, I believe, in the profession, that which renders it a fit place for a dreamer and a writer."

In the second passage he describes a contrivance for comfort in the winter.

"To-day we have had a squad of men at work in our tent. We have dug a cellar about two feet down in the ground, and have scraped a deep hole in one corner, with an opening outside the tent for a fireplace and chimney. The arrangement is a great success. We have more room; and then, too, it is a pleasure, for it is a novelty, [Stanley inserted a phrase in Greek characters here], one remembers. It is not a bad thing to be a troglodyte. It is attacking the very citadel of death and terror to live in a grave and build a fire at one end! According to Bayard Taylor, I shall take the most luxurious repose possible tonight. He somewhere sillily remarks: 'There is no rest more grateful than that we take on the turf or sand, save the rest below it.' To be sure, I do not put much confidence in what he says, for I can testify that a very mean straw mattress even is far preferable to the bare earth. Faith! there is little to choose between that and a grave. Indeed, the one is uncommonly apt to lead to the other. But, dear me, what a jumble of demi-puns. Well, mother Earth and daddy Clouds have been hard at work all day turning Virginia into a mortar-bed, and the army will have to stay in camp awhile, if it does not wish to get stuck in the mud."

I could wish to say something of the tenderness of affection with which he loved his friends, and to quote something from those words which were a last precious legacy to the friend to whom they were sent, and to whom he says that he understands him so well that "I don't know how, it seems as if I was you somehow." But over that part of his loving nature and his true, manly heart we will drop the veil.

In the short year of his military life he lived a lifetime. Experience shows that the war has made men go upward fast or downward fast; but the progress was fast. Stanley grew into maturity. His letters read like those of a man of middle age; and with this growth came a child-like simplicity and gentle trustfulness which it is now inexpressibly pleasant to recall.

In the middle of August his valise came home. It contains one unfinished letter to that friend to whom his heart had always been open. Although written some months before his death, it contains his last words; and none could be more touching. He thus quietly speaks of his religious faith, that "point which had been settled long ago": —

"When the lesson of submission has been so completely learned that regretful thoughts never steal into our hearts, why should we live longer? Is not our appointed work accomplished then? Yes, I think I believe that now. I think I understand that submission is the only real virtue. I have often puzzled my head to get at some unselfish motive for being good, and now I am quite sure that I recognize what religion taught long ago. I have not got to the point from which started long years ago by the same road that led thither. Mine has been longer and dustier and more perplexing. I have groped thither through Heaven only knows how much of darkness and doubt, and scepticism almost. But I am quite certain that we are journeying now upon the same track, hundreds of miles ahead and yet wonderfully near me too. is Great Heart, I think, who has come back to show me the way

We must remember the beautiful saying of Massillon : 'On n'est pas digne d'aimer la veYite quand on peut aimer quelque chose plus qu'elle.'"

by Edwin H. Abbot.